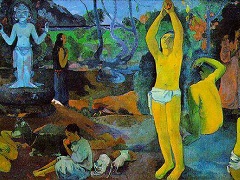

Vision After the Sermon, 1888 by Paul Gauguin

In the summer of 1888, young Emile Bernard, his head full of theories that would overturn Impressionism, arrived in Pont-Aven where Gauguin had been working. Out of their meeting was born "synthetism," of which Vision After the Sermon, painted at that time, was the first complete result.

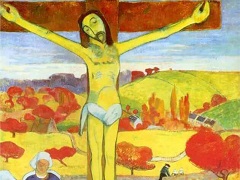

It is a bold picture, a religious painting conceived and executed with the faith of a convert to a new artistic credo, but the two faiths were not unrelated in Gauguin's mind: "A word of advice," he wrote to Schuffenecker, "don't copy nature too much. Art is an abstraction; derive this abstraction from nature while dreaming before it, and think more of the creation which will result [than of the model]. This is the only way of mounting toward Godoing as our Divine Master does, create." Thus Gauguin has imagined a peasant vision induced in minds of great and simple faith by a Sunday sermon. In the foreground the peasant women, their backs turned to us, excluding us, as it were, from what they alone can see; in the background the symbolic struggle, two tiny figures on an expanse of unreal red that might be a field or might be the sky. Everything is painted in flat colors separated by clearly drawn contours in a way that is at the opposite pole from Impressionism. There is no color modeling, no blurred edges, no softening of form or hue by an intervening, unifying atmosphere. The unmodu-lated areas of white, black, blue, and red startle the eye by their contrast; the middle ground has been deliberately omitted to separate the peasants and their vision. For the first time Gauguin gives his composition a pulsating unity by employing throughout the curving, rhythmic contour that is to recur in so many future paintings.

The picture's sources are many: the bent diagonal of the tree trunk and the downward perspective, as well as the outlines suggest the Japanese woodcut generally, while the wrestlers are from a particular print by Hokusai'; the outlines and the flat, bold colors are akin to medieval stained glass and the woodblock of the images d'Epinal, both devoted to religious subjects; Impressionism is still evident in the way the frame cuts off the figures. All these sources have been put at the service of a new conception.

"I believe," wrote Gauguin to Van Gogh, "I have attained in these figures a great rustic and superstitious simplicity. It is all very severe."